• NOTE: Barry Meadow's article was originally published in his best-selling book Money Secrets At The Racetrack. It makes reference to USA tracks, etc.

Picking winners at the races is no big deal. Just bet all the public favourites and you'll cash one-third of your bets. You'll also lose your money. To win, you must find overlays.

Our opposition is the public. Every bet we make is a contest between our perception and theirs. If we can find enough discrepancies between our opinion and the crowd's, and we're right often enough, we'll win.

How much better must we be than the crowd to succeed? Battling a 20 per cent grab for (tote) takeout and breakage, we must be 25 per cent better than the crowd to break even. With a 23 per cent takeout, we must be nearly 30 per cent better.

The crowd consists of many elements. The vast majority are casual fans, many of whom can barely read a Daily Racing Form (if they buy one at all). They bet on hunches and numbers, or follow crude, ill-informed handicapping theories.

Though this group is large in number, it is only a partial influence. A small circle of big-money regulars heavily affects the (US) pools. A survey at Aqueduct Racetrack not long ago, for example, showed that 42 per cent of the money is bet by only 1.5 per cent of the players. And it's this clique, which includes some high-rolling casual fans but is also made up of professional gamblers, expert handicappers and racing insiders, that is tougher to beat.

Before the advent of cash-sell machines, you had to bet at tote windows of particular denominations, e.g. $10 win, $2 show (place), etc. Surveys at the time showed that players at the big-money windows far outperformed those at the $2 windows. Recent surveys have shown that late money outdoes early money, and most big bets go in close to post time.

At some small tracks, this 'smart money' might come from only a single bettor. And mob psychology sometimes takes over after a big punch on a horse. If an animal hovers around 3/1 and then, with a minute till post, skips the 5/2 mark to drop directly to 2/1, many bettors consider this a providential sign and then follow the hot money, driving the horse's price down even further.

My most fervent hope at the track is that the horses I like will get absolutely no tote action whatsoever. It's no thrill to spend an hour finding an apparent longshot who, at trackside, is banged down to 7/5. Who needs him? I'd rather play someone who is getting less action than I think he deserves - not more.

There's always the temptation to follow the hot money, particularly on a horse with no form, on the theory that somebody knows something. And, at times, somebody does. In the long run, though, following your own opinion is the way to make money at the track, if your opinion is good enough.

We compete against a crowd that is constantly adjusting and correcting its earlier odds. And it's a tough opponent. As a whole, the public is a good predictor of race results. More than half a dozen studies, involving tens of thousands of races, have found these conclusions:

- The lower the odds, the more likely a horse is to win. The surveys show that 3/5 shots win more than 4/5 shots, 9/2 shots do better than 5/1 shots, etc.

- The public overbets longshots and underbets favourites. Betting every public fav, you'd lose half the takeout; betting every 50/1 shot, you'd lose far more than the takeout. When you play longshots, you're getting the worst of both worlds, higher risk and lower return.

Though the crowd does pick plenty of winners, the fans also make plenty of mistakes. It's not necessary to win every race, or even a majority. Since we demand a 50 per cent bonus for our plays, all we need to make money betting races is to find small errors. We probe the crowd's line for vulnerable spots to attack.

For example, we make a horse 4/1, meaning we think it will win this race 20 per cent of the time. The crowd dismisses him at 9/1. Even if he wins only 14 per cent of the time, meaning we were overly optimistic in our assessment, we will still show a profit.

THE MEADOW 50% PLAY

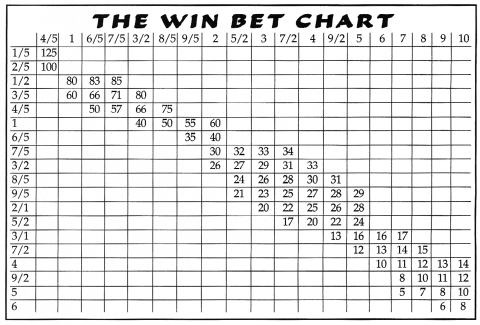

The Win Bet Chart lists win bets assuming a $2000 win-bet capital, not $2000 total capital. It assumes this is the amount you have to risk on win bets only. Looking over my own betting records, I find that about 40 per cent of my betting action is to win. If your betting is similar, then the chart can be used as is if your total betting capital is $5000 (since 40 per cent of $5000 is $2000). If your capital is larger, or smaller, adjust these amounts by the appropriate percentage.

The numbers were derived by assuming that instead of your odds line being accurate, it is only accurate to the point where you will earn a 6 per cent edge on minimum overlays, 8 per cent on overlays of one extra column, 10 per cent on overlays of two extra columns and 12 per cent on overlays of three extra columns, and then using half the Kelly (optimal betting) recommendation rather than the full Kelly for security. Thus, if it is in error, it errs on the

side of safety.

The small bets in the chart (e.g. $6 to win on a horse you rate 6/1 who goes off at 9 / 1) won't bring you a million dollars in a week. However, their conservatism makes it unlikely you will go bust. And, assuming your handicapping improves with experience, your capital will grow larger which will enable you to increase your bets.

Even though the bet sizes may seem tiny, your handle (turnover) for a particular night could still be large. On a single race, for instance, you might bet $40 to win, another $40 in the exacta, $150 to place, and $20 in the daily double. Make six such bets a day and you've put $1500 through the windows.

And if your long-term records show you to be a player who wins at a much larger advantage than our estimate of 8 to 10 per cent, you can safely bet higher amounts. Note that the largest bets are those with the greatest chance of winning - the horses you list at even money and below. Although your bets also increase as the edge becomes larger, the key is the frequency of wins, not the size of the advantage.

When betting overlays, beware the free lunch factor. When you decide that a horse is an overlay, you're pitting your judgement against that of the public, and the fans are not all oafs. If you rate a horse at 2/5 but the public makes him 7/2, you've probably overestimated the horse.

Your overlays will usually come from lesser mistakes - the public has failed to recognise a crucial negative trainer change, overrated a pacer's recent suck-along fast mile, overlooked a dog's three week layoff, etc. These errors cause the prices of the other entrants to drift upwards.

Some players don't like to bet an overlay because they feel the horse is cold; either he's not well-meant, or he's gone off form since his last race. While it's true that occasionally you will bet on a 9/5 shot who should have been evens but isn't because the horse is 'dead', my records show that longterm profits come from betting overlays

indiscriminately, without trying to guess the stable's intentions.

Horses win every day with not a single penny bet on them by anyone connected with the stable.

The numbers on the left refer to your own odds line. The numbers at the top refer to the available odds. If, for example, you make a horse 6/5 and the crowd lists him at 9/5, you would bet $35. If they send him away at 2/1, raise your bet to $40.

If an overlay is not listed on the chart (e.g. your 3/5 shot goes off at 8/5), play the highest listed number, in this case $80. The numbers assume the race is average (let's say rated B on an ABC scale of interest in a race). If you rate a race as C, bet less; if A, bet more. If your capital fund is more or less than $2000, adjust these figures accordingly.

NEXT MONTH: Barry Meadow tells how you can bet two overlays a race and keep in the profit market. Barry is the author of two acclaimed books on harness handicapping, Success At Harness Racing and Professional Harness Racing, and currently produces Master Win Ratings and a monthly newsletter. You can contact him at TR Publishing.

Click here to read Part 2.

By Barry Meadow

PRACTICAL PUNTING - JULY 1998