More than six months have passed since PPM printed an interview with the legendary US handicapper Mark Cramer.

His earlier books are a little hard to find, but his most recent work, Value Handicapping, subtitled "The art of making your own line and identifying overlays", is still readily available.

This is part one of an extract from the book, which is a chapter introducing the thinking behind Cramer's "value betting" philosophy. The book has received acclaim from many in the industry, including PPM's own correspondent, Barry Meadow.

The primary goal of the book, Value Handicapping, and the only real objective for a serious horseplayer, is to acquire and refine the skill of identifying overlays: horses whose true probability for winning significantly exceeds the amount of betting action they receive.

For example, a horse whose true probability is 4/1 but is being bet at 9/1 has been underestimated by the betting public. He should pay $5 to win but if he wins, he'll pay $10. This is a whopping 100 per cent overlay.

Similarly, a horse that should be 2/1 on, but flashes at 2/1 against, should pay $1.50 but will return $3 if he wins. If you bet only this type of "value" horse, longshot or favourite, there is no way to lose, because the excess payoffs more than make up for those races you don't win.

Remember, all bettors, even favourite players, lose more than they win. For a profitable bottom line, their wins must return more money than their losers lose, and this can only occur if the winning horses return a greater price than their probabilities warrant. This is the essence of value wagering.

On the other hand, if you bet underlays, even if they are the most-likely winners, walking up to the window to collect on winning bets will simply prolong the agony; in the long run you will be destined to lose.

The classic underlay illusion is the horse you've picked that is going off at 6/4. He is clearly the best horse in the race. You know that, and so does everybody else. But the results of horse races are not deterministic. If the 6/4 horses you bet on should be 2/1 or 3/1, even if they are the best horses in their respective races, you are preordained to lose money on this type of horse, because your winners will not return enough to pay for your losers.

The positive side of the same coin is when your 6/4 shot should be even-money. In this case you have a classic overlay.

When, then, is a contender good value (art overlay) and when is it an underlay and therefore a bad bet? Serious players with an investment mentality answer this crucial question by making a personal odds line.

The line tells them what each horse's post-time odds should be, based on estimated probabilities, so that they immediately recognise whether any of their contenders are worth a bet (paying off more than they should).

A personal odds line establishes a proportional hierarchy of probabilities in a given race, from the most-likely to the least-likely winner. Odds as we know them are really a hierarchy of probabilities. For example, even-money is equivalent to a 50 per cent chance. Assume that you have learned to estimate accurately when horses should be 1/1. By assigning evenmoney to a horse on your personal odds line, you are really saying that theoretically, if the same race were run 100 times, your horse would win 50 and lose 50.

Consider this subset in your betting portfolio: the horses you've estimated to be even-money. You follow a basic rule; only bet horses whose odds are at least 50 per cent higher than your personally assigned odds.

In the case of your even-money estimates, you can only take them at 6/4 or above. Using $1 wagers, after 100 bets, your investment totals $100. Your least possible profit is calculated by multiplying the minimum $2.50 acceptable payoff times the 50 winners based on your accurate even-money appraisal. Your return: $125, for

a $25 profit and a 25 per cent return on investment ($25 is 25 per cent of $100).

Let's look at another theoretical case. If you make your contender 3/1 and your assessment is accurate, it means that he will lose three times for every one time he wins, equivalent to losing 75 times out of 100. The ratio 3:1 equals 75:25, or 25 wins out of 100 races: 3/1 odds equal 25 per cent.

In order to compensate for the negative track take and for one's own margin of error, handicappers using a personal odds line will require a minimum 50 per cent overlay, in terms of odds. Examples: the horse you've assessed at evenmoney on your line cannot get bet unless it's going off at 6/4 (one-and-a-half to one) or above. For your 2/1 line horse, you'd require a minimum of 3/1 on the board. For your 3/1 line horse, you cannot bet unless it is paying off at 9/2 or better.

Contenders are defined as horses that are 6/1 or less on your line. A horse you've made 6/1 cannot be bet unless it is paying 9/1 or better. But a horse that is 8/1 on your line is a non-contender and cannot be bet even at 99/1.

Why was your 8/1 horse not a contender? Once you get into the higher odds ranges, your chance for judgmental error increases, while the real difference in probabilities decreases. The difference between a 10/1 (9 per cent) probability estimation and a 15/1 (6 per cent) chance is so narrow percentage wise that there is too little margin for error. So if you've estimated a horse to be 49/1 and he's going off at 99/1, that's not an overlay because there's only one percentage point difference between 49/1 (2 per cent) and 99/1 (1 per cent).

The core of Value Handicapping will explore various ways to construct an odds line. Constructing an odds line is a question of translation. You will be translating your handicapping insights into numerical probabilities. In other words, you'll be translating ideas into numbers, the way a teacher would grade an essay test.

We refer to a "PERSONAL odds line" because each handicapper is different, and two competent and creative handicappers may come up with distinct personal odds lines. If each of these horseplayers uses an insightful handicapping methodology and bets only on overlays, then they will both be winners in the long run, even when their odds lines clash in the short run.

FORM AND CONTENT

A personal odds line is made of two components: content (the handicapping method) and form (the odds line itself). Content determines form.

The old adage of garbage-in-garbage-out must have been invented by personal odds line makers. Form (the odds line itself) cannot make up for bad handicapping that goes into it (content). Sloppy handicapping or race analysis that mimics the public will cancel out the strategic advantage of a betting line. Even good handicapping in the absence of a sense of value will produce a negative bottom line.

This writer does not intend to be dogmatic about personal odds lines. I recognise that there are a few players out there who somehow have an inherent sense of value and do not need to make their personal odds lines to discern overlays. But more typically, most competent horseplayers achieve unsatisfactory results precisely because they fail to link their handicapping to measures of betting value.

A moderately competent handicapper who measures betting value with a personal odds line will win more money than a superb handicapper who does not.

The personal odds line provides this crucial measurement. Even players who do not plan to make odds lines for the rest of their handicapping lives will benefit from the discipline of doing it over a meaningful period of time, the way one learns to drive an automobile by consciously following each guideline until the procedure becomes automatic.

Detractors of the personal betting line strategy say: "I told ya so! Meadow, Mitchell, and Roxy Roxborough (the foremost linemaker in the US) all make a line on the same race and come up with different probabilities. That proves personal odds lines are subjective."

Of course they are subjective! There are many ways to win at the races. There is, however, one sure way to lose, and that's by betting underlays.

The track take makes it all the more necessary to bet only on overlays. Assume that at your track, with the take and breakage factored in, you are betting into the win pools with a 17 per cent disadvantage. This is the percentage that is skimmed off the top of what would have been equitative mutual payoffs based on the public's preferences.

This means that in order for bettors to break even, they must receive a long-term average of 17 per cent better than fair mutual payoff. In order to earn a 10 per cent profit, they must receive an average payoff of 27 per cent better-than-fair mutual payoff. Given the subjective imprecision of anyone's and everyone's personal odds line, demanding a 50 per cent advantage before betting is a safe and rational strategy.

In attempting to gain this investment advantage, the handicapper's main enemy is the guy next to him in the grandstand or off-track betting establishment. Overcoming the track take is only enough to break even. Beyond that, the horseplayer must intellectually outwit the betting public.

Overlays, like an 8/1 that should have been 3/1, emerge when you are right and the public is wrong. Common sense dictates that you cannot outsmart the public if you handicap with the same information and methods as the

public. To be effective, the handicapping content that goes into a personal odds line must rise a methodology that is comprised of (a) information underused by the public; and/or (b) a style of analysis that is generally shunned by the betting public.

Consider that, if your handicapping depends on Beyer figures, your most likely winner at 2/1 personal odds will probably be 6/4 on the board (an underlay) because the tote board odds are determined by the public consciousness, and the public overestimates the importance of Beyer figures.

But if you discover an underused breeding angle that projects a horse to stretch out successfully after poor sprints and low Beyer figures, your 2/1 personal odds may be 8/1 on the board (an overlay).

MECHANICS

The personal odds line is constructed on the basis of 100 percentage points. The odds we ascribe to a horse are translated into percentage probabilities. Example: odds of 6/4 mean that a horse has a 40 per cent chance to win, because the ratio 6:4 is the same as 60:40. Should you ascribe 2/1 to a horse, you've indicated a 33 per cent probability.

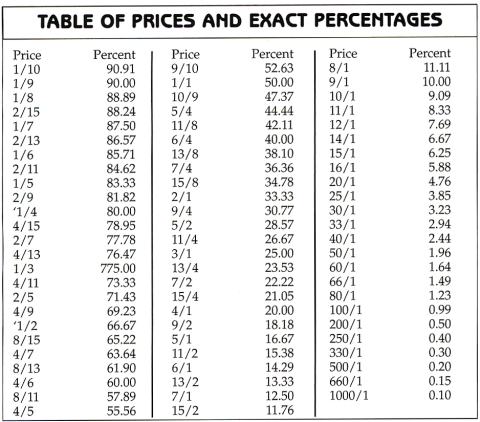

Examine the handy odds/ percentage conversion table below, which will be your partner in odds-making until you've memorised it.

There are two ways to use this table. You can begin with percentages and then translate to odds, by saying that John Henry has a 50 per cent chance to win and therefore is even-money while Thunder Gulch should have a 14 per cent chance and thus is 6/1 on your line. Your line is not finished until the total of the percentages for each horse in a race adds up to 100.

This extract from "Value Handicapping" was compiled by PPM's Tasmanian-based contributor Steve Wood. The book is available from the publisher, City Miner Books at the web site http://pages.prodigy.net/cminer/indexbody.html.

Click here to read Part 2.

By Mark Cramer

PRACTICAL PUNTING - NOVEMBER 2002