It was very refreshing to read Ynez Ybarbo's two articles in the July and August issues of Practical Punting Monthly. Early in her first article, Ynez mentions Andrew Beyer, one of the gurus of US racing, and the fact that his methods do not work particularly well on turf racing.

In his excellent book Beyer On Speed, Beyer writes about the time he spent in Australia, firstly in 1988 and then for a longer period of about four months in 1990 / 91.

Despite doing an abnormal amount of preparation for his trip down under to tackle turf racing Australian-style, Beyer found the going tough and two and a half months into his trip was behind the eight-ball, finally ending a mere $500 in front, before expenses, after his extended stay.

Beyer wrote the following: "I did not assign my lack of success to the foreignness of the racing ... but I didn't understand the game fully. One possible explanation occurred to me ... (that) the critical factor lies between turf racing and dirt racing ... because I had learned virtually all my lessons about handicapping from dirt races."

However, as Ynez points out, that does not mean that Beyer does not have a message to tell to those who want to learn about speed handicapping. So, in a practical sense, what can we learn from what Ynez Ybarbo told us about USA turf racing and how does it measure up against what happens in Australia?

The first observation that is mentioned is in regard to weights and the fact that many horses do not appear to be unduly disadvantaged by rising sharply in weight from their previous run.

Similar research done in this country by myself and others has also made similar observations. In fact, over a year ago in response to a reader's question, I stated that a horse's weight increase is a far more positive factor than a weight decrease, quoting the following statistics:

- Horses dropping in weight by 3.5kg or more: 6.2% strike rate.

- Horses dropping in weight between 0.5kg and 3kg: 7.4% strike rate.

- Horses carrying the same weight: 7.8% strike rate.

- Horses rising in weight between 0.5kg and 3kg: 11% strike rate.

- Horses rising in weight by 3.5kg or more: 13.9% strike rate.

There are many instances of where horses have risen sharply in the weights in direct comparison to their opposition and won again. A few months ago, the 5yo Western Australian mare Tribula won twice at Group 3 level in open weight-forage events, and then raced again at Group 3 level at her next start, but this time in an open handicap.

In the Belmont Sprint in mid-June she was meeting seven opponents that she had beaten at her last start, with all seven being better off at the weights from 2kg up to 7.5kg, including both the second and third placegetters from that previous race.

Conventional weight handicapping techniques would have ruled her out of contention, which is what most backers thought, as she went out as a $10 shot, but that didn't stop her winning yet again, beating both those previous placegetters by a bigger margin than before, even though they were better off at the weights to the tune of 5.5kg and 7.5kg respectively.

Ynez describes her experiences with times and how her analysis disclosed that in races of a similar class virtually identical average times were returned over all common distances, no matter if the races were run at Belmont, Churchill, Laurel or the lightning fast tracks of southern California.

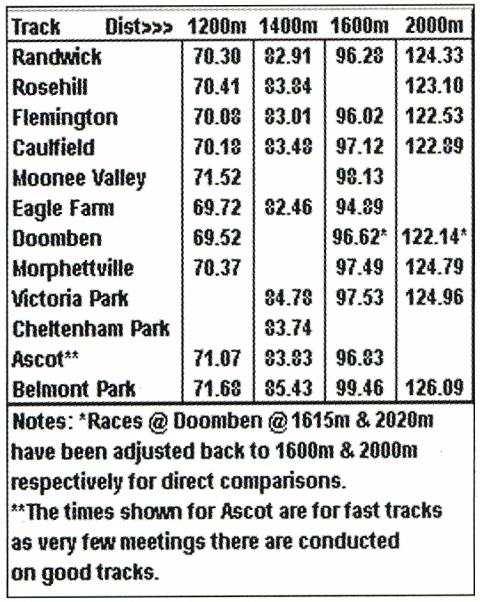

Given the nature of turf tracks in the US, I suppose it is not surprising that the average times for common distances are not as diverse as they are in Australia, as the following tables, for the major metropolitan tracks, disclose (based on Open Handicaps on good tracks and excluding 2yo races).

Significant variances of times across all distances occur due to very different track layouts and surfaces - from the wide open spaces of Randwick and Flemington; the tightness and StrathAyr sand-based all-weather track of Moonee Valley; and the lushness of Belmont Park in Perth.

As a matter of interest, the average weight carried, after taking into account apprentice allowances, by the winners of metropolitan Open Handicaps over all distances is slightly under 54kg, more or less the same as what it was five years ago.

While not being able to use times to distinguish between the better type of horses running at one track and those racing at other tracks, Ynez concludes that the same is not true with horses of a lesser class the claimers - with times clearly demonstrating that some are better than others, depending on where they are racing.

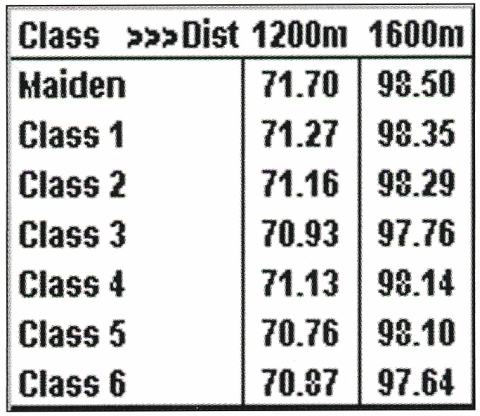

The issue of using average times to distinguish between the classes is not so clear-cut in Australia and while the trend favours the better class races, there is some blurring in this area, as the following table discloses, which is based on 1200m and 1600m races run on good tracks at provincial (not country) meetings.

At 1200m, Class 2 races are run as fast as Class 4 races, which are run slower than Class 3 races, with Class 6 races run slightly slower than those at Class 5 level.

At 1600m, Class 4 and Class 5 races are run slower than Class 3 races, which are only slightly slower than those at Class 6.

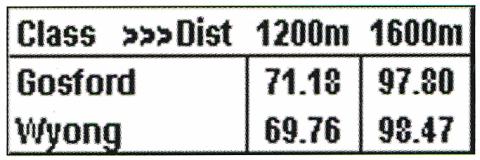

However, the problem in Australia of using average times to distinguish where the better horses are running is perhaps better illustrated by comparing the times run at two of the major provincial tracks in New South Wales, Wyong and Gosford.

The following table is based on Class 6 races run on good tracks at the two venues.

Given that the two tracks are comparable in their standard of races, the average times for 1200m races indicate that those run at Gosford are about nine lengths inferior, while the times for 1600m indicate that those run at Wyong are about four lengths inferior. How long is a piece of string?

Ynez's quest then turned to the effect of weight on race times, with her research concluding that, at the four most popular race distances, a little over 70 per cent of above average times were recorded by horses carrying weight within 2.5kg of the top weight.

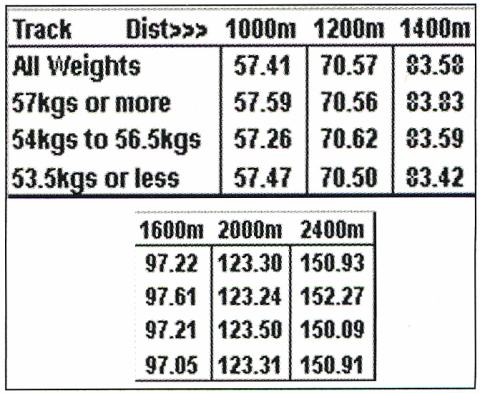

Such is not the case in Australia, with times over the shorter sprint races indicating that, by and large, weight appears to have little effect, while at distances of 1400m or longer its effect does play a part, as the following table discloses (based on Open Handicaps on good tracks at metropolitan venues, excluding 2yo races).

The times recorded for the 2400m races need to be treated with some caution, as they are based on only limited data. The fact that there is a significant variance between winners carrying 54kg to 56.5kg and those carrying lesser weights, which run slower times, may be nothing more than an aberration.

Perhaps of more significance is the average time for winners who carry 57kg or more over the longer trip of 2400m, as in these instances they are running about eight lengths slower than the average time for this distance.

I have a good friend in Perth, Tony Acciano, who is a rabid weight/class handicapper and has long maintained that as the races get longer, weight has greater effect. In fact, he still uses the Rem Plante ADE chart published back in the late 1960s, as well as being a disciple of the Weight Distance index (his own invention), and the table above may well have vindicated his opinion.

Ynez then raises the point that horses competing at higher levels have the ability to win carrying higher weights than those racing at lower levels and this would appear to be the case in Australia, as the following table discloses (based on open aged races, which excludes 2yo and 3yo only races).

Even though Group 2 winners carry on average 0.8kg more than Group I winners, the trend is definitely towards those running at the higher levels being able to carry the heavier weights and indeed my observation of the actual winners of Group 2 races are that many also performed at Group 1 level with success.

Towards the end of her second article, Ynez discusses trainer habits, stating this area is now her primary focus. It is not too hard to understand why.

However, this area of form analysis has many angles: from a stable's betting intentions to the ability to place their horses in suitable races, or the ability to step horses up sharply in distance, etc.

One area of trainer habits that has been used, particularly in the UK for some time, is the trainer/jockey combination. I know of one professional over there who has used this angle with great success for many years.

Over the past year or so, the trainer/jockey combinations have also become popular in Australia, with the printed media such as Sportsman, as well as the Internet sites Racenet and AAP Racing and Sports,

providing these statistics.

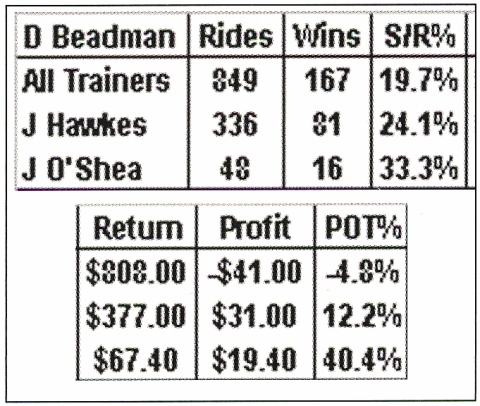

One of Australia's most successful jockeys is Sydney-based Darren Beadman, but following him blindly would have been a foolish and expensive exercise, as betting each and every ride he had for the first 11 months of the 2002/03 racing season would have resulted in a loss on turnover (LOT) of 4.8 per cent, and included a losing sequence of 30 rides.

However, when considering just two trainer/jockey combinations as indicated in the table below, a somewhat different outcome could have been obtained.

As well as the 16 winners Darren Beadman rode for John O'Shea, he also rode a total of 34 placegetters (including the winners) from his 48 rides, returning a level-stakes profit of 10 units (POT 20.8 per cent) for betting the place on TAB Ltd. Clearly, when trainer John O'Shea engages jockey Darren Beadman to ride, they are a formidable combination - a good example of trainer habit or intention.

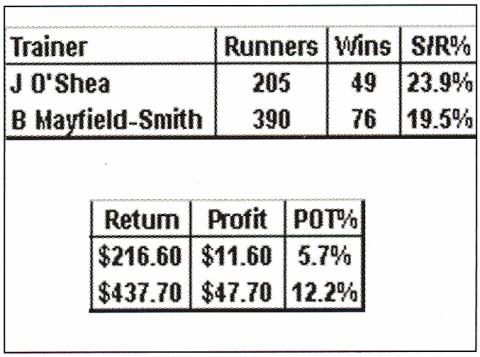

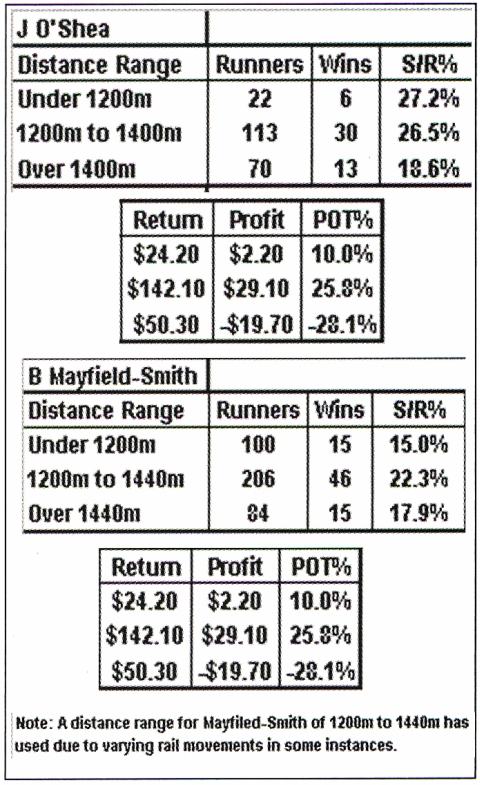

Finally, we look at the ability of some trainers to win within a certain distance range, in particular two of the finest trainers in Australia, Sydney-based John O'Shea and Melbourne-based Brian Mayfield-Smith.

The following table shows their overall statistics for the first 11 months of the 2002/03 racing season.

Without any further analysis, backing all of their runners would have been profitable, but when we break down their statistics into distance ranges, an even better result could have been obtained.

However, considering only horses trained by either up to 1440m, the results speak for themselves and, in the case of Mayfield-Smith, only backing his runners in the 1200m to 1440m range would have resulted in a more than acceptable return.

My theory on why "boutique" trainers like O'Shea and Mayfield-Smith do so well with sprinters is that they have a small number of horses in their stables and it is essential that they have success on a regular basis to ensure that their operations remain viable.

They simply do not have the time to persevere with staying types in the same manner as some of the larger training establishments.

In conclusion, while there are a number of differences in the style of racing between what occurs on the turf in the US and Australia, overall Ynez Ybarbo has provided PPM readers with some valuable insights and a few pointers to how we can go about the task of becoming better punters down under.

By E.J. Minnis

PRACTICAL PUNTING - SEPTEMBER 2003