Punters may bet all their lives with bookmakers and yet remain 'in the dark' about the way in which the knob-twirlers operate. As one punter told me recently: "All I know about prices is that I should take the highest one I can about the horse I'm backing."

In a sense, he is right. In the prices market at the racetrack, the bookmaker is a seller of odds and the punter is the buyer. In its own way, bookmaking and punting is a true example of the voluntary forces of the free market. A bookie must offer some value or he will have no takers. The more value he can offer while, at the same time, ensuring himself a profit, the more money he will stand to make.

It's not easy being a bookie, up there on the stand and taking bet after bet and trying to keep a tight hand on your profit and loss account! Punters don't place their bets conveniently! There is always a rush of money for a particular horse and a bookie has to exercise care and judgement under pressure in determining how much money he will take at a certain price for any horse. Too much money can tip the scales in his carefully planned percentages and cause him to be betting to losing figures.

The key principle of making a book is relatively simple. If a race has 12 runners then each of them has a chance to win. Of course, each has a different chance of winning. Some have big chances, others have little and these chances will be reflected in the odds the bookmaker offers. He may think two of the 12 have strong prospects, five possess moderate chances, while the other five have little or no chance of winning. With this in mind he works out his prices and offers them to the punting public.

What he does, though, is offer them in such a way that no matter which horse wins, he (the bookie) will make a profit. Most bookies aim for a 10%-12% mark-up on a race. Once he has taken out 4%5% to pay for his taxes and costs, he has a net profit of between 7%-8%.

He has to aim to achieve this profit over the eight or nine races of the program. His problem is that in racing, nothing is clearcut. He is going to have races in which he loses (when a hot favourite, well backed by all and sundry, wins). His eventual aim, over a period of 12 months, is to ensure that his percentage mark-up works for him in that span of time. He may lose on a meeting, but he will win over 52 meetings.

Punters, too, should bear this in mind when they bet. Sadly, few do.

The bookmakers' most lethal weapon, naturally, is percentage. He can always give himself a percentage edge over the majority of punters. The punters he doesn't like are those who try to play him at his own game - by making their own 'true' markets on races and betting only on overlays (those horses at prices longer than their projected true chance of winning).

A term in bookmaking is called 'betting round' and this happens when at bookie holds, say, 100 units and is up for paying out the same amount no matter which horse wins a particular race. This is breaking-even time.

A bookie will want, though to bet 'over round'. This is where he holds more than 100 units for each 100 he has to pay out.

He does this by offering prices that basically are under what he considers a horse's true winning chance happens to be. If he thinks a horse is a 6-4 chance he will try to sell its price at 5-4. He will try to sell you a 4-1 chance at 3-1 and so on. It's a simple, clean-cut business when you think about it. Both sides are trying, in a way, to rip the other off.

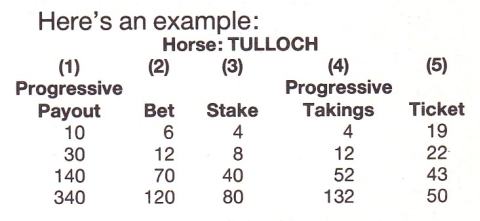

Let's look at the way a bookie's sheet looks (win only). In his first column is the total from adding Columns 2 and 3, and this shows what the bookie will pay the punter if this horse wins (in other words, the bookie's liability). The second column is the bookie's stake, the amount he actually bets. The third column shows the punter's stake, the amount of his bet on a horse. In the fourth column is the progressive total of Column 3 - the total amount the bookie holds on any particular horse. In the fifth column is the ticket number.

Here's an example:

At this point, the bookmaker stands to pay out $340 on Tulloch, while his takings total $132 on the horse. By glancing at the payout total and the takings column, he can quickly assess which horses he has to lay more to balance the book in his favour.

The bookie's penciller keeps a running total of the money that the book is holding on all horses in the races. He writes this in the right-hand margin of the big betting sheet. By the time a field jumps away, the bookie will be standing to make varying amounts on each of the runners should they happen to win. With some horses, he will lose if they win because he has taken bets on them whose totals add up to more than he holds on the entire race.

A bookie's gross turnover figure on the race may be $10,000. He then immediately subtracts the 21/4% turnover tax which he has to pay to the government. This would leave him with a total of $9,775 to cover the betting activities of the race. If say, an outsider got up he might be only standing to pay out about $1,000 on him. That would give him a big profit on the race. Then again, he might have laid one horse for about $11,000 and if it won he would be looking at a substantial loss on the race.

A bookie is in a spectacularly uneven business. He works to a plan, naturally, but the best-laid plans can easily go astray when punters get to work. He may lay a horse at far shorter or much longer odds than its eventual starting price and depending on whether he has laid firmers or easers, his end percentage may be a very slim one.

Quite often, bookies are caught with plunges on horses at big odds. They continue to be zapped throughout betting, even as they reduce the odds in the face of the onslaught. If you carefully note a bookie's prices throughout betting, you will see that his percentage will go up and down. He may open betting with a nice, 112% book but then the betting starts and in many instances the betting on certain horses is such that although the bookie may finish betting with a percentage of, say, 109%, he in actual fact has a very small chance of winning on the race.

So, really, it's not just a case of a bookie getting up on his stand and making heaps of money. He does have an edge over the punter, but he has to be very, very shrewd and calculating - and lucky -to keep ahead of the game.

A growing number of bookies these days tend to be punters themselves, in that they will 'take on' horses they believe are over-rated. You'll find that bookies sometimes are more than happy to accept all the bets they can on a short-priced horse - believing, obviously, that it is under the odds and cannot win. He will, in essence, take a risk on the horse and lay it for more than he will hold on the race. If it loses, he is a big winner. If it happens to win, he cops a loss on the race.

There are many people in the bookmaking fold who see this as the way of the future in bookmaking - the bookies bet heavily against what they consider to be poor value horses while protecting with low prices the horses they feel can win the race.

How many bookies do you read about these days who employ a small army of form clerks to keep detailed records, and to prepare 'true' price lines? This is because over the past few years, punters have become much more intelligent than they used to be. They are now looking for value in betting and they won't take a price they consider is under the odds. They are squarely fighting the bookmakers with analysis and form study.

Bookies say their percentage margins are failing away. One leading bookie told me: "I'm lucky if I can make 2% or 3% a year. You've got to be an opinion bloke - you have to be prepared to spend many, many hours looking at form, videos, photos and guides to frame your own good chances in a race, and then you have to be prepared to take the risks associated with having an opinion.

"A good bookie is able to close shop on the good chances and blow out on the roughies."

There are still many hundreds of bookmakers in Australia and it's a fair guess to say that each one of them has his own, individual way of operating. One bookie can make a certain method of operation work for him, while another would go broke if he tried the same thing. What is known is that when the betting action begins, the bookmaker is all on his own. He has to assess the chances, make decisions in the hurly-burly of frenetic betting activity, and to keep on winning he has to be a little bit inspired.

Another important thing to remember about bookmakers is that they do receive very good information. They keep close tabs on barrier trials and unreported 'jump out' trials. They hear when a certain horse has made sudden and dramatic improvement on the trialling track. They know when a certain horse cannot win. They know when a certain horse can win.

Bearing these points in mind, punters can capitalise on the bookies' knowledge by watching closely how they frame their betting markets. Are they allowing a horse that was hotly fancied in the morning markets to drift right out? Did they open the horse a point over its morning price? This could mean the horse has a ‘slow' on it and that the bookies are happy to take any number of bets on it. Avoid these horses like the plague.

By StatsmanPRACTICAL PUNTING - AUGUST 1986