If wagering markets were efficient then it would be equally profitable to bet on any racing horse whether it is the favourite or a longshot.

However, the “longshot” bias in wagering has been around since the first satchel swinger hitched his pony to a rail. In simple terms punters tend to overbet longshots and underbet the favourites.

Over the years there have been many studies into the “phenomenon” that constitutes “longshot” bias.

In this article, I will refer to three of these studies and their conclusions, as well as presenting some tables highlighting the longshot bias existing in horse racing in Australia today.

The first study examined is the one made in 2000 by Russell Sobel, of the Department of Economics, West Virginia University, and Travis Raines, of the Department of Economics, University of North Carolina.

They presented two theoretical explanations for the favourite-longshot bias, finding that the most popular explanation for the bias, the risk preference model, cannot explain the data as well as an information-based model, in which the bias depends on bet complexity and the information possessed by punters.

As mentioned, market efficiency requires that betting on racetrack favourites is as equally profitable as betting on the longshot, or any other horse. However, this is not the case as the returns on betting the favourites are higher than the returns on the longshots.

Sobel and Raines found that less-informed, or “casual” punters tended not only to bet significantly less per person but also less heavily in the exotic betting markets than do regular or “serious” punters.

One of the differences they found was that the “casual” punter tended to bet more over the weekend than what they did at the midweek meetings (and I guess that is why Sunday racing has become so popular in Australia).

For instance, they found that the average betting per person per race is much higher midweek than at a weekend, suggesting a higher proportion of serious punters. For every dollar spent by the average weekend punter, the midweek punter spent between $1.10 to $1.18 dependent on the meeting, with the extremes being as high as 50 per cent per person per race midweek verses the busiest weekends.

On average, the serious punters also tended to concentrate more heavily on the exotic bets involving multiple selections.

On Saturdays they found that the favourites receive an average of 26.3 per cent of win bets, yet at the midweek meetings they captured 29.2 per cent of the bets. For longshots, the opposite occurs with an average of 5.4 per cent being bet on Saturdays, while only 3.7 per cent of all bets are for the longshot to win at the midweek meetings.

Some previous studies have suggested that the favourite-longshot bias becomes more severe as the racing day progresses. This conflicts with most standard models of risk behaviour as traditional models suggest that as wealth declines throughout the day punters should become less risk-loving.

Sobel and Raines’ research disclosed that there was an upward trend towards longshot betting in the last race – the “get out” stakes.

Their conclusion was that as the proportion of casual (less-informed) punters enter the betting pool, the share of that pool bet on the longshot rises, moving the market further in the direction of a favourite-longshot bias.

In addition, more complex bets tend to demonstrate more of a favourite-longshot bias because higher bet complexity functions similar to having less-informed punters.

Essentially, casual punters bet too evenly across the possible outcomes thus underbetting the favourite and overbetting the longshot. This same effect is present on very complex bets where it is hard for punters to understand critical relationships.

In a more recent study in July 2003, Marco Ottaviani, of the Economics Subject Area, London School of Business, and Peter Norman Sorensen, of the Institute of Economics, University of Copenhagen, looked at the issue of how late informed betting impacted on the favourite-longshot bias.

According to Ottaviani and Sorensen, “information-based” punters have an incentive to protect their private information and (in most instances) bet at the last minute, without knowing the bets simultaneously placed by the others. Once the distribution of bets is revealed, if bets are more informative than noisy, all punters can recognise that the longshot is less likely to win than indicated by the distribution of bets.

What they propose as a result of their research is that there is a “new explanation” for the favourite-longshot bias, which is due to the simultaneous last-minute betting by privately informed punters whereby other punters are, in effect, shut out of betting on these “plunge” horses as the betting markets close.

Ottaviani and Sorensen claim that their explanation is compatible with the observation that late bets contain a large amount of information about the horses’ finishing order, as documented by Asch, Malkiel and Quandt (1982).

For the third of the studies, we turn to William Ziemba and Donald Hausch, who many years ago wrote one of the all-time best selling racing books when they published Dr. Z’s Beat The Racetrack.

The basis of the “system” contained in the book was exploiting the inefficiencies in the US parimutuel place and show betting markets.

Part of the authors’ thesis was that inefficiency in the place and show betting markets occur because of the greed factor whereby punters go looking for value in other pools and their (the punters’) inability to estimate the true value of place and show bets.

Paradoxically, the same greed factor is present in the win pools and despite the potential for seemingly large dividends; many of these types of bet are in reality offering huge underlays.

Ziemba and Hausch assumed that the public were very good at estimating the true probability of each horse’s chances of winning, that is 2/1 shots win more often than 5/2 shots; that 5/2 chances win more often than 3/1 shots – and so on.

In addition, the lower the odds on a horse, the greater the returns on that horse over the longer run. For example, if you bet $1 on each horse whose odds were 2/5 the long-term return would be 95.5 per cent. By contrast, if you bet $1 on each horse whose odds were 20/1 the long-term return would be a mere 78.7 per cent (my analysis on Australian races produces a different outcome).

Similar to other studies before and since, Ziemba and Hausch concluded that the favourite-longshot bias is quite pronounced. In their study, horses whose odds were 1/5 actually return a slight profit.

The authors present it as evidence of the average fan’s tendency to overbet longshots and to underbet strong favourites in order to satisfy their “greed” for large profits. To paraphrase the authors, there isn’t much profit or fame derived from betting on a 1/5 favourite that is the best bet of the day, so the average fan looks to horses and combination wagers with low probabilities and high payoffs. Unfortunately, the favourite-longshot bias for win bets is not enough to make positive profits by betting on all horses in any single odds category.

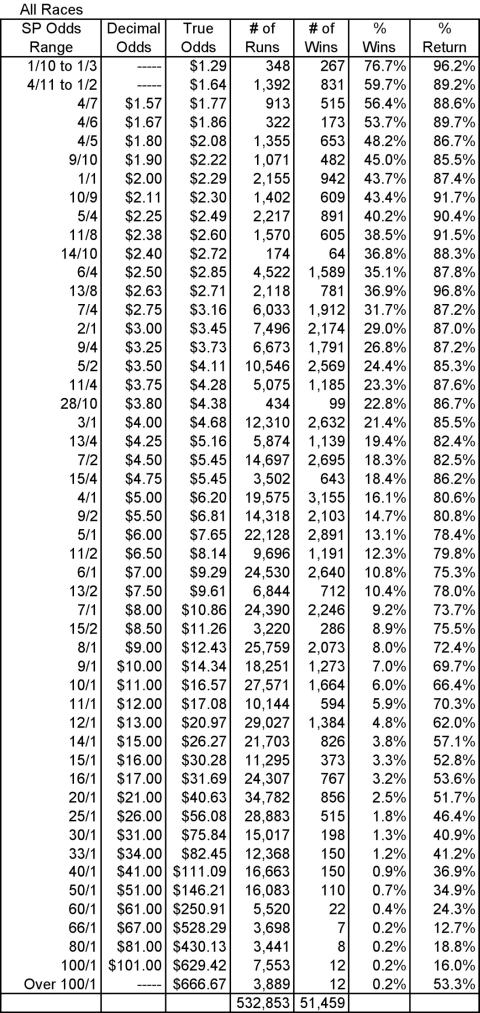

Based on over 500,000 individual horse runs and 50,000 races, I have analysed the proportion of horses which actually win at different odds. As part of this analysis I have calculated what the true odds should be for each value of SP odds, for all races, and then extracted just the non-handicap races such as the set weights, weight-for-age and similar type events.

The overall return amounted to 421,417 units which translates to a return of 79.1 per cent, which in effect means that on average punters lost 20.9 per cent of every dollar (based on SP odds).

The analysis also discloses that once horses are at longer prices than about 4/1 to 9/2 then the returns drop below the average return of 79.1 per cent.

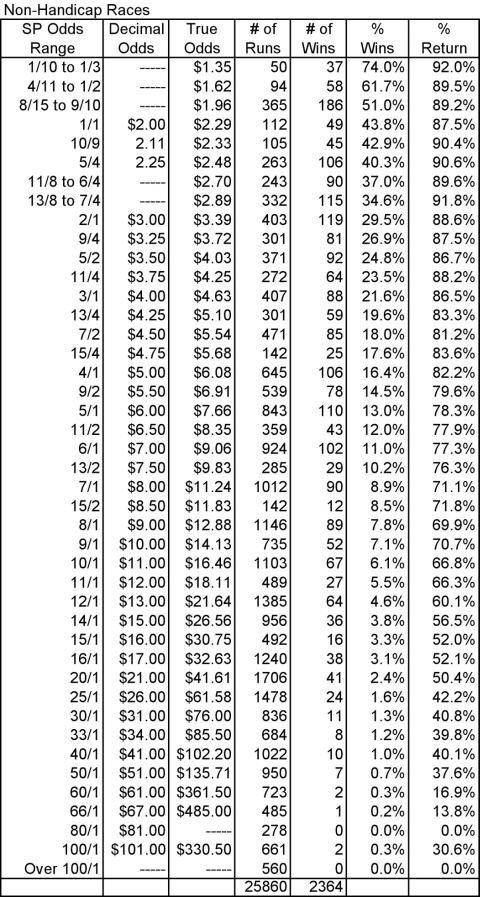

The analysis of the non-handicap races discloses that the return on runners at a shorter price is slightly better than for the handicap events.

The conclusion drawn from this up-to-date analysis is that the longshot bias is as evident today as it was many years ago.

One of the benefits of betting exchanges is that they offer, in many instances, the most efficient betting market available anywhere – better than the totes and better than the bookmakers.

Often betting to over-rounds of somewhere between 101 to 105 per cent and with liquidity on offer between those wanting back or lay, there are advantages to be gained by using those prices as the basis for other types of betting, such as the exotics.

Because of the lower over-rounds, betting exchanges generally offer better odds than those offered by the bookmakers or totes.

But, what is a “fair” price for a horse with a SP of say 10/1? A punter would require about $16.50 for such a bet to be representative of its true winning chances, which may be obtainable on a betting exchange, but most unlikely elsewhere.

With horses that are more in the market, say an even money SP favourite, $2.30 would be representative of its true chances of winning, while close to $3.50 would be required about a 2/1 SP chance.

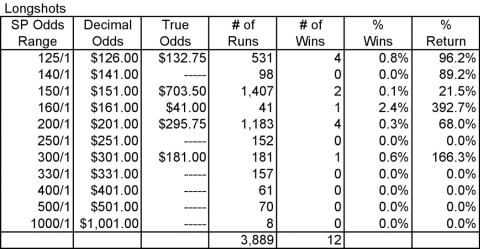

Finally, a somewhat sobering table detailing the 3,889 longshots priced at over 100/1.

Just a mere 12 winners, but is there a light at the end of the tunnel, those horses starting at both 160/1 and 300/1 both returned a healthy profit!

By EJ Minnis

PRACTICAL PUNTING - JULY 2004